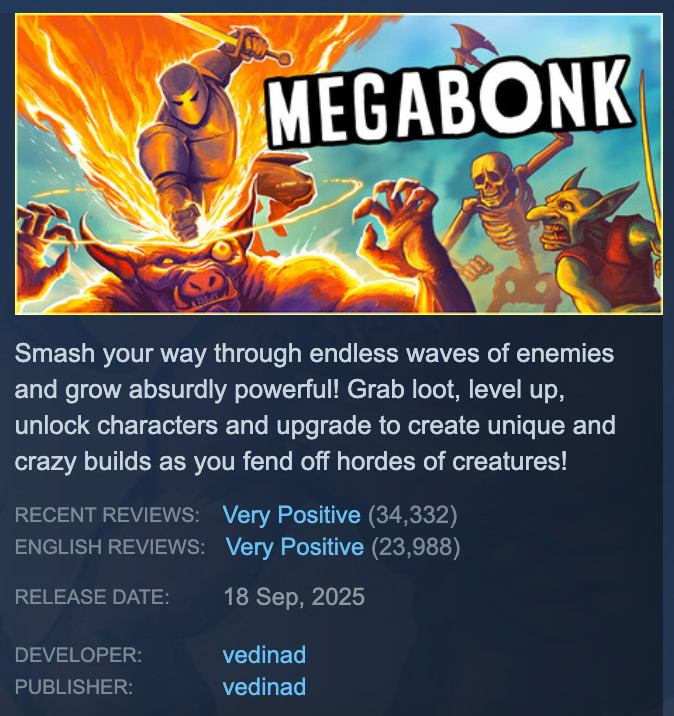

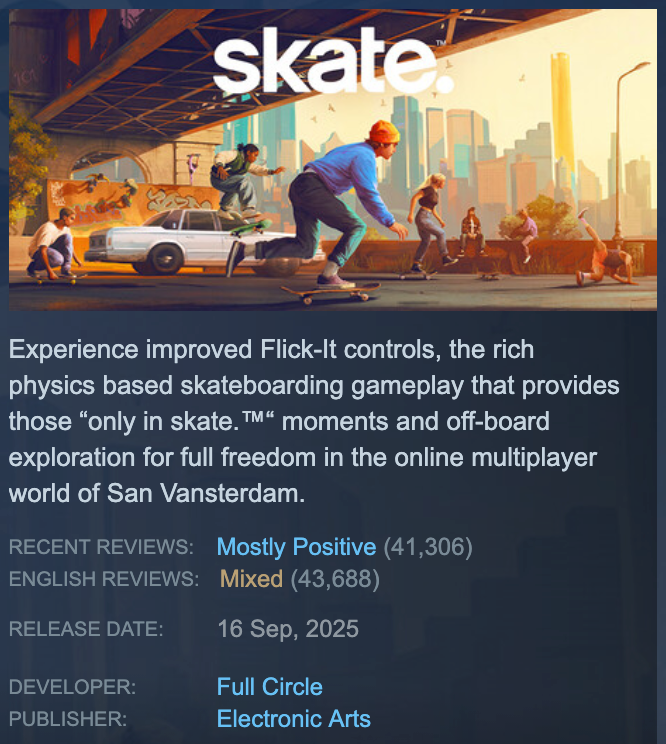

Megabonk vs Skate: How a $10 Indie Game Outplayed EA’s Triple-A Giant

This article explores the contrasting success of two currently viral games: the indie hit, Megabonk, and the free-to-play AAA title, skate. Both games thrive on an addictive core gameplay loop and massive replayability, yet they speak to two entirely different futures for the gaming industry.

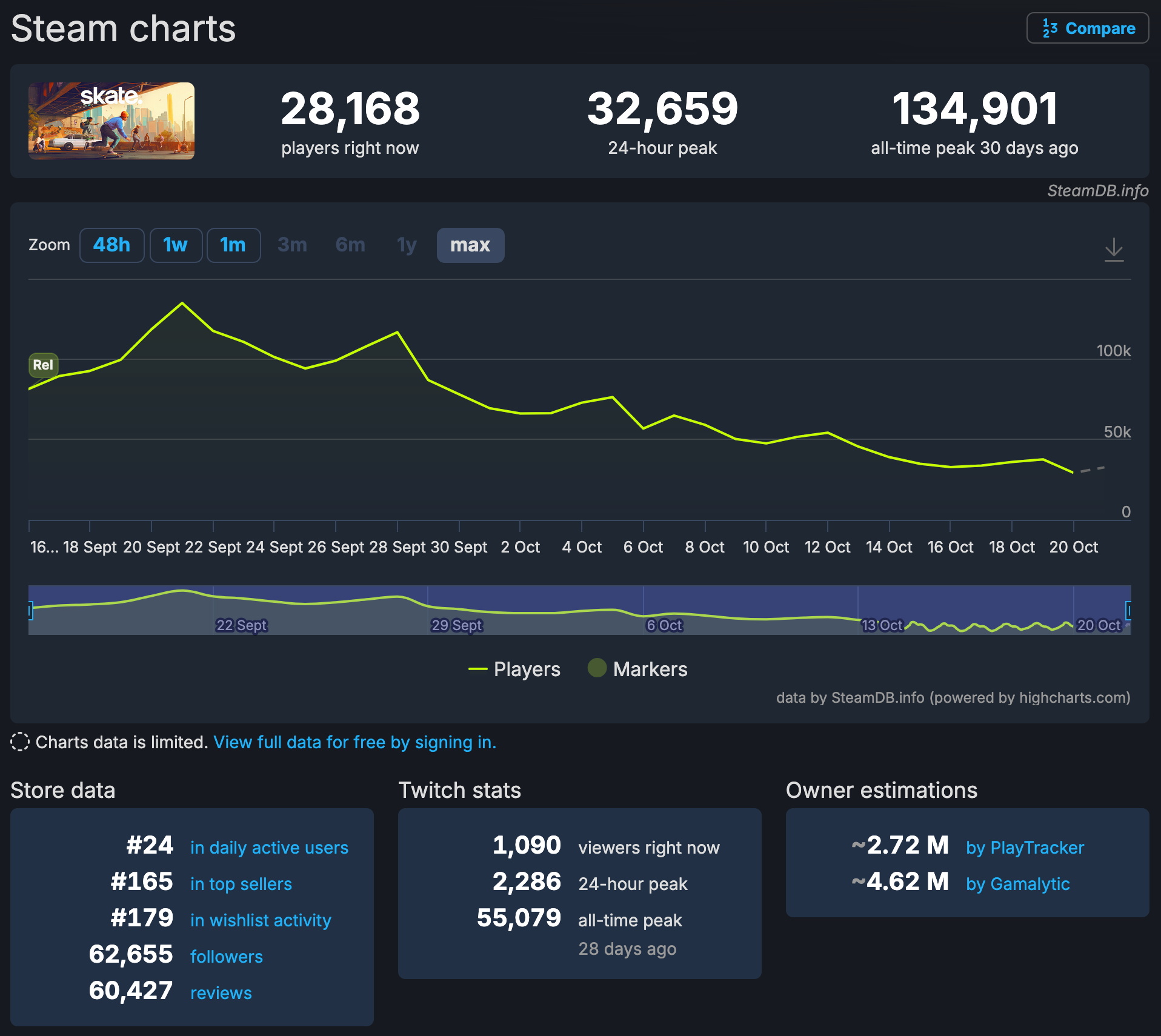

The gaming world is locked onto two wildly different titles that dropped within 48 hours of each other. skate., EA’s long-awaited, free-to-play reboot, launched on September 16th. Then, just two days later on September 18th, Megabonk showed up out of nowhere a $10 indie game made by a solo developer and completely stole the spotlight.

Both games claim to chase the same ideal: a tight, endlessly replayable gameplay loop built purely for fun. But once you scratch beneath the surface, the similarities end. What you actually get is a clear split in modern game design Player-First vs Profit-First.

We’re going to break down how two games built on the same core idea ended up representing two opposite sides of the industry. One is backed by a billion-dollar publisher and shaped around monetization. The other is a chaotic indie title that only cares about being stupidly fun and somehow, as you’ll see later, it outperformed the giant across multiple metrics.

This is gaming’s David vs Goliath moment. We’ll dig into how both games launched, how players reacted, how money shaped their design choices, and why Megabonk might just be the loudest wake-up call the industry’s had in years.

Because if Megabonk proves anything, it’s that in 2025, you don’t beat AAA with more money you beat it by making something people actually want to play.

1. The Core Loop: Empowering Mastery vs. Unrewarded Repetition

A great core loop is the repeatable cycle of action, challenge, reward, and progression that keeps a player engaged. Both games nail the immediate Action, but diverge wildly on the philosophical intent behind their systems.

Megabonk: The Loop of Empowering Mastery

Megabonk is a Roguelike Survival game where the core loop prioritizes mastery and curiosity.

| Phase | Description | Player Intent |

| Action | Move and automatically attack ever-growing hordes of enemies across a 3D arena. | Survive. |

| Reward (Internal) | Collect EXP and choose random upgrades to create synergistic, game-breaking "builds." | Curiosity & Power Fantasy. |

| Progression | Death is a lesson learned. Every run provides new knowledge about effective builds and item synergies. | Skill Development. |

| Meta-Progression | Spend resources on permanent unlocks (characters, weapons) to ensure the next run is functionally novel. | Genuine Advancement. |

In Megabonk, the experience is designed to let the player "break the game," an internal reward that fuels virality and word-of-mouth. Even with mastery, random factors ensure no two games are the same, and success is never guaranteed, constantly driving players back to the loop for the satisfaction of building something unique.

skate.: The Loop of Endless, Static Grinding

The core loop of skate. is built on Physics-Based Trick Chaining in a Social Sandbox. While the skating mechanics are brilliant, the structure is designed for retention in a live-service environment.

| Phase | Description | Player Intent |

| Action | Master the physics-based Flickit controls to perform tricks across the open world. | Skate. |

| Challenge | Complete repetitive missions, time trials, and challenges in the persistent online world. | Engagement. |

| Progression Flaw | After mastering the core controls, the game offers little in the way of novel, developer-created advancement. Mastery hits a content ceiling. | Frustration. |

| Reward (External) | Earn minimal in-game currency or basic cosmetic items. Desirable items are often tied to the premium store. | Monetary Friction. |

The game succeeds at the Mastery Loop (getting better at tricks) but fundamentally fails at the Content Loop. Once players become proficient, the game effectively punishes mastery by offering limited meaningful advancement, leaving players to generate their own fun in the sandbox. This creates a friction point that pushes players toward the game's storefront, where the only consistent progression is cosmetic and paid.

2. Accessibility: Runs on a Potato vs. The Hidden Hardware Tax

The differing philosophies are most apparent in their technical approach and cost barriers.

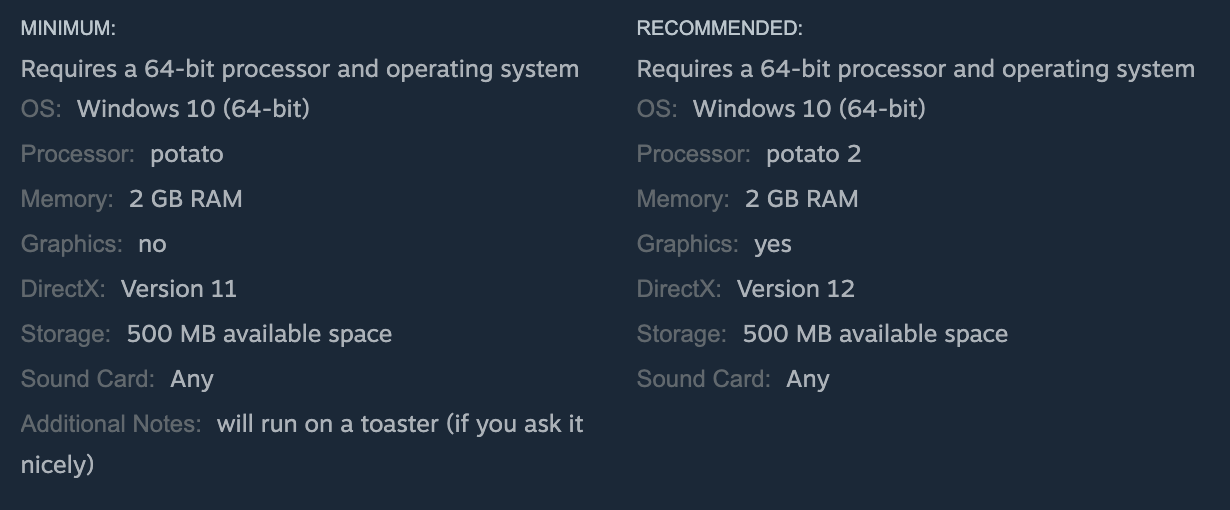

Megabonk: Maximum Accessibility

Megabonk was built with a clear intent: The widest possible audience should be able to play the game.

- Low Cost: The $10 one-time price grants access to the full, non-monetized experience.

- Minimal Specs: The requirement of a "potato" for a processor speaks volumes. The game prioritizes the integrity of the gameplay loop over graphical fidelity, ensuring it is accessible to gamers globally, regardless of their hardware budget.

- Developer Engagement: The solo developer’s rapid, continuous updates and bug fixes reflect an immediate responsiveness to the community, fostering a relationship where the game feels like it is being "made by the community."

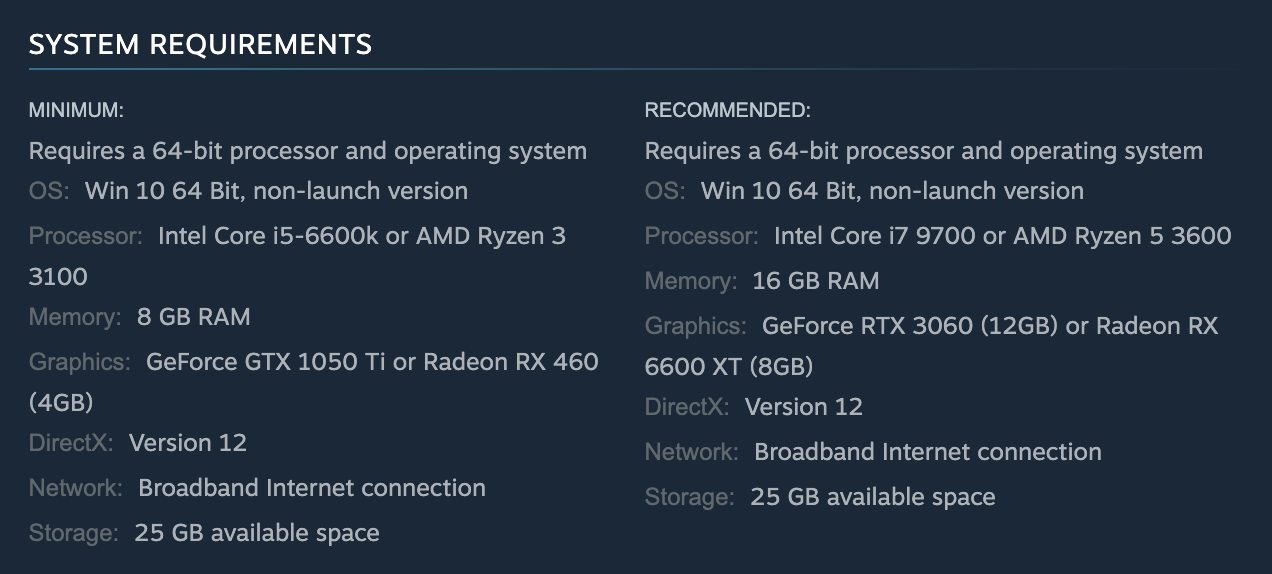

skate.: The Console-First Barrier

While skate. is "free-to-play," it establishes a higher, often hidden, barrier to entry, especially for PC players.

- Monetization Focus: The "free" entry is a hook for the live-service model, pushing players toward purchasing premium cosmetics, currency, and the Battle Pass.

- The Controller Tax: Despite being released on PC, the game requires a controller to be played effectively. Furthermore, official communications regarding controller support have suggested only official controllers are guaranteed to work. For PC players, this transforms the $0 entry point into a $40-$60 hardware tax for a new controller, completely negating the perceived cost advantage of a "free" game.

- Quality of Life Sacrifice: This focus on a console-first control method, combined with an immense focus on high-fidelity graphics via the Frostbite engine, suggests that the priority was not on the quality of life for all players (i.e., universal PC controls) but on delivering a high-spec, retention-focused experience.

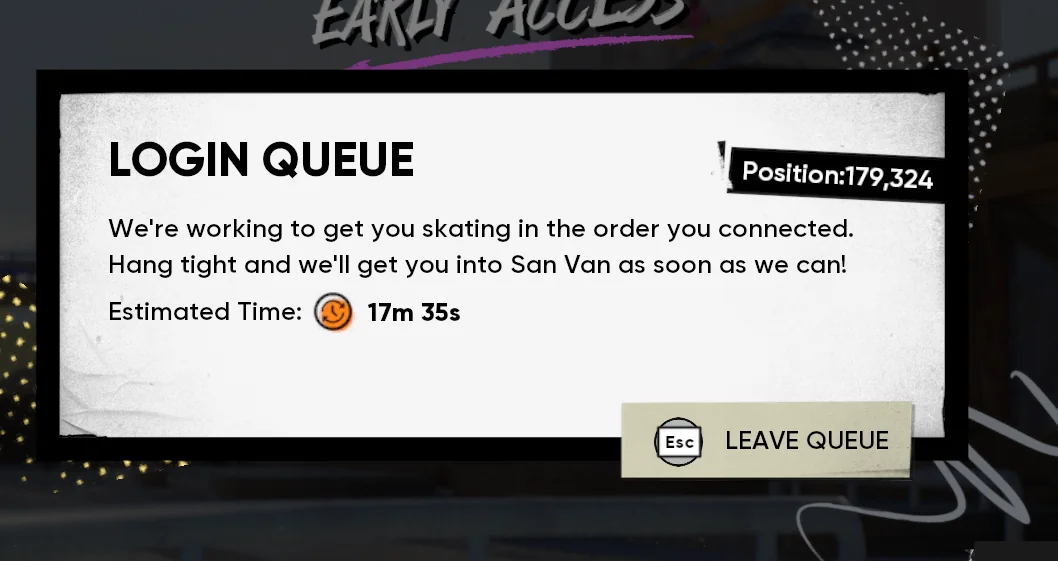

- The Live-Service Friction Paradox: Despite being a fundamentally solo experience (freestyle, challenges), the game's always-online, massively multiplayer structure creates a frustrating and unnecessary in the way of outrageous wait times. This includes being forced into insanely long queues (sometimes over 20 minutes) just to access the core sandbox.

3. The Virality Divide: Authenticity vs. Curated Performance

On the surface, both Megabonk and skate. have massive digital footprints, achieving significant view counts across streaming and social platforms. However, the nature of the content surrounding each game is dramatically different, illustrating their core philosophies and the surprising failure of skate.'s forced multiplayer to foster true community.

Megabonk: The Journey of the Authentic Attempt

Megabonk has thrived on long-form, authentic content that fosters a sense of shared community and learning:

- The Shared Journey: Megabonk streams and videos often record entire playthrough attempts. Viewers tune in to witness the player's progression, celebrate the luck of the draw in their build choices, and learn from their mistakes.

- Unique Narratives: Each run is a unique, unrepeatable "story" of survival. The content is an authentic document of a challenge, including the near-misses and moments of struggle. This builds a powerful, empathetic connection between the creator and the audience, turning the single-player experience into a shared, collective obsession with strategy.

- Community of Strategy: This focus on the process over the result transforms the viewing experience into a collective discussion about new strategies, builds, and tips, reinforcing the game's loop of "a lesson learned each time."

skate.: The Isolation of Curated Performance

skate.'s digital presence, in stark contrast, is dominated by short-form, highly curated content that emphasizes flexing competency and achieving fleeting, singular moments of glory:

- The Highlight Reel: The content is heavily focused on short, viral clips, which feel almost performative, almost like unauthentic Instagram content. Long-form videos, while present, consist almost entirely of highlight reels, cutting out hours of missed attempts and repetitive practice.

- Unauthentic Skill Display: By eliminating the "stale moments and misses" and the struggle that makes real-life skating rewarding, the viewing experience becomes a sanitized, isolated display of skill. This focus on only showing the perfect results creates an isolating sense of "bragging" rather than a shared experience.

- The Paradox of Isolation: Despite being an always-online, massively multiplayer game, skate.'s content model is fundamentally individualistic and competitive. It asks the player to perform in a space shared by hundreds, yet its digital footprint is one of isolation, showcasing my trick, my challenge, and my competency.

The Verdict: Two Roads to Virality

The contrasting journeys of Megabonk and skate. illuminate the two possible futures for games focused on endless replayability:

Megabonk proves that a focused, player-first design with a generous, empowering core loop and low barriers to entry can create authentic, explosive virality and profitability. The genuine, unedited narrative of the single-player run successfully builds an organic community of shared strategy.

skate. proves that a legacy franchise will sacrifice the depth of its progression and the universal accessibility of its platform in favor of a profit-first, live-service model. Its forced multiplayer structure and curated content model result in a toxic mix of server friction and digital isolation. The player may pay $0 to start, but the game is fundamentally designed to erode the value of the player's time until they pay to feel really any sense of reward or acquire meaningful cosmetics.

One game offers mastery leading to empowerment and shared storytelling; the other offers mastery leading to a storefront and curated isolation.

Final Thoughts

At the end of the day, none of this should be complicated. A good game isn’t about how many millions got poured into it, how realistic the lighting is, or how many people were on the dev team. It comes down to two things: is it fun, and did the people making it actually listen? That’s it.

Both of these games solidified that point in what to do and what not to do. They’re not perfect, but they each have their unique strengths and weaknesses. People will argue over which one is better, and that’s fine. But without a doubt, one of them excelled in so many ways that most triple-A studios keep missing: they made something people actually want to play, not just something they want to sell.

So if you haven’t touched either game yet, go try them. Seriously. And for the big studios watching, this should serve as a wake-up call and hopefully this stings. Because this is the clearest proof yet that “more” doesn’t mean better. More funding, more graphics, more hype, none of it matters if the game itself is hollow.

This feels like a win for gamers and indie devs alike. Not just because indie or smaller teams are better by default, but because it proves the industry can still get it right when it strips things back to what matters. Fun beats flashy. Every time.